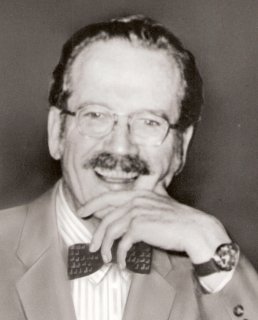

Charles o terwilliger, Jr – a Biography by his son

Charles Ostrander Terwilliger Jr. was born in Pawtucket Rhode Island, March 22nd 1908. His father was Charles O. Terwilliger Sr. His mother was Josephine Edgerton Badeau. C.O.T. Sr. was a chemist and inventor. The family moved to various locations in the northeastern US and spent some time in Germany, finally moving to Mt. Vernon, NY. Charles attended Phillips Andover Academy and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

While at MIT, he met his wife Roberta Emily Thornburg who was his sister’s roommate at Radcliffe.

His stay at MIT coincided with prohibition. Using his natural mechanical skills he built a car out of spare parts. He called it “the lobster pot”. Calling on his natural business skills he began using the lobster pot to transport grain alcohol from his father’s lab in Mt Vernon for sale to students in Cambridge.

On December 7th 1941, I was three months old and my father was stationed on the U.S. west coast in an Army coastal artillery unit. Before being shipped to the Pacific his unit was given a final physical. Charles did not pass the physical and was returned to civilian life.

He had some difficulty finding a job in engineering so he took a job in Manhattan as an advertising space salesman for MacFadden Publications. They were the publishers of pulp magazines for the women’s market – the precursors of today’s soap operas. Titles included “True Story” “True Confessions” and the most popular “Photoplay”. Eventually MacFadden Publications became MacFadden-Bartel Publications. At this time the Terwilliger family – Charles and Roberta, their daughter Anne and son Robert lived just outside Bronxville New York, a small town one-half hour from Manhattan either by commuter train or car.

The job of an advertising salesman was highly stressful. A necessary ritual of the business at this time was to use his expense account to take advertising space buyers out to lunch, usually someplace that became an up-scale nightclub after dark. He was well known at “The Stork Club” and “21”. While Charles did manage to avoid the pitfall of the “three martini lunch” he did develop the syndrome called “advertising ulcer” at that time. His doctor suggested he get a hobby to allow his mind to get off the constant pressures of his job.

Charles was a natural mechanic and had always been interested in clocks. He joined the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors in January 1950 as member #819. In 1951 he became Chairman of the NAWCC Membership Committee. A natural post for an advertising man. Read a PDF from a 1951 NAWCC Bulletin on COT’s initial membership efforts. While Chair of this Committee NAWCC membership increased dramatically – earning him some distain from the “Good Old Boys” for the number of “ordinary collectors” he had brought into their Association.

His job had one advantage in that he was able to spend a lot of time moving about New York city entertaining or meeting clients. He began to frequent the auction galleries looking for clocks. Auction galleries were to become an important asset in his horological future. While buying a few good pieces he concentrated on French and German clocks with movements he could use to practice repair techniques.

Once he had accumulated a large number of movements, his entrepreneurial nature kicked in again and he started a business – “Charles Terwilliger Old French and German Clock Parts”. His stock of parts was acquired by cannibalizing his large stock of movements. His customer base was advertisements in the NAWCC Mart.

He began to frequent the U.S. Postal Service auctions for movements.

Whenever the post office paid the insurance amount for a damaged parcel the parcel contents were sent to a central location in New York. There they were put in large lots that were sold at public auctions.

There were plenty of lots of damaged clocks. Many were cheap electric clocks in broken cast spelter cases. There were also always a large number of 400-Day Clocks – most of which were broken (probably just the domes) when they were shipped from Germany by GIs who had bought them from Post Exchanges to send home.

By the mid 50’s he had accumulated a large and organized collection of “modern” (post WW II German) 400-Day Clocks – at least one of each make and model he had found, as well as many older clocks. At this time collectors did not have much interest in torsion pendulum clocks so he was also able to purchase antique and unusual examples at the regular auction galleries. These older clocks formed the nucleus of the Horolovar Collection and the photographs found in the later editions on the Repair guide.

Charles was aware of the problems that made 400-Day Clocks unpopular with clock repairmen. They were poor timekeepers and the principal problems were associated with the suspension spring. Most of the German movements themselves were quite uncomplicated and well made.

There was no sense or order to the suspension springs available to the repairman. The clocks occasionally came with spare springs. These early springs were made of a steel or bronze alloy. The suppliers of clock repair items had no point of reference to differentiate between clocks.

Charles called on some resources he had maintained from his years at MIT. Tests determined that the currently available springs had an inconsistent modulus of elasticity. In other words the available springs would stiffen or weaken, some considerably, with changes in temperature. This was a primary source of the timekeeping problems.

Some more research provided an excellent option for a new alloy for suspension springs. One with a constant modulus of elasticity – Ni-Span-C.

Ni-Span-C is a nickel-iron-chromium alloy made precipitation hardenable by additions of aluminum and titanium. The titanium content also helps provide a controllable thermoelastic coefficient, which is the alloy’s outstanding characteristic. The alloy can be processed to have a constant modulus of elasticity at temperatures from -50°F to 150°F (-45 to 65°C). Used for precision springs, mechanical resonators, and other precision elastic components. Standard product forms are round, strip, tube, pipe, and wire.

Data provided by the manufacturer, Special Metals.

It should be noted that the material did not require heat treatment to provide the desired characteristics.

Having selected a potential alloy, he sought a facility to manufacture the springs. He successfully approached the Waltham Watch Company, which became Waltham Precision Instruments in 1957. For more than a century, these companies operated in the same historic building in Waltham, Massachusetts and the suspension springs were drawn and rolled on the same machinery that was used to make hairsprings for the magnificentt Waltham Watches.

The Ni-Span-C wire was first drawn through diamond dies to a specific diameter such that when rolled to a specific thickness the width of the resulting spring was always .016 inches. The constant width allowed assumptions about the effects of variations in thickness.

Now the experimentation began. He acquired some sample springs from his manufacturers and systematically installed them in the various clocks he had collected, including a number of rare and unusual clocks – First to see if they would work at all, then to see if they would keep time.

They did work and they did keep time.

Having achieved satisfactory performance with the sample springs the stage was set to embark upon the business adventure that was to shape the rest of his life.

What should he name his product? He combined the prefix “horo” (from the Greek hora = time) and the suffix “var” from the metal “Invar” – another alloy with similar thermal characteristics.

Thus Horolovar.

Horolovar – While a clever syllabic juxtaposition, and if examined it pronounces as it’s spelled, “Horolovar” was often not intuitively pronounced.

How to pronounce Horolovar

The Beginning ⚬ Horolovar Spring ⚬ The 70s and 80s ⚬ Epilogue