The Horolovar Collection More Info

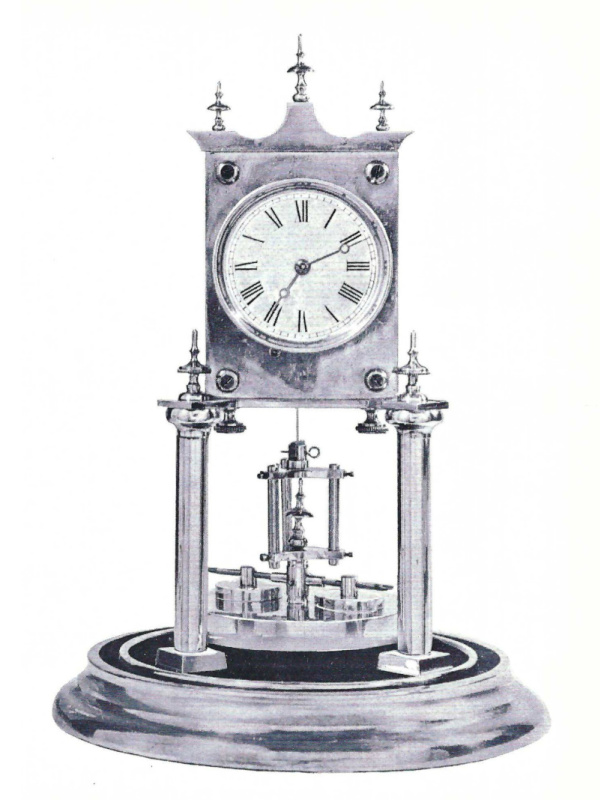

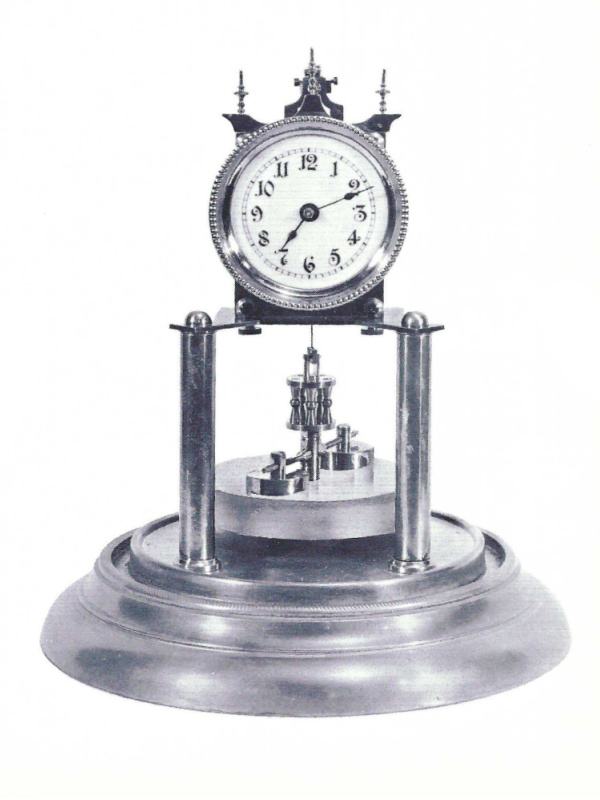

No. 1

1885

This is the oldest clock in the collection; it was made by Jahresuhrenfabrik. Although its movement differs little from the original 1880 Harder patent, the clock has certain refinements, not all of which, however, were continued in subsequent models. The dial is of high quality porcelain. The bezel, the squares at the base of the columns, the columns, column finials and the movement platform are all of sturdy construction and undoubtedly made from unusually high grade brass.

The pendulum is an intermediate design between the one in the original Harder patent which is a flat disc (see page 122 of the appendix), and the ultimate design with decorative crown as in Clock No. 6 and in many others that follow.

The velvet covered wooden base, with brass only on its perimeter surface and on the collar around the inner circle of the glass dome groove, is typical of the clocks made prior to and immediately after 1900. Note that the pendulum is attached to the bottom of the suspension spring unit with a pin. The “hook” connection followed a few years later.

A dwarf model of this clock with a simple disc pendulum similar to the one shown in the Harder patent is known to exist.

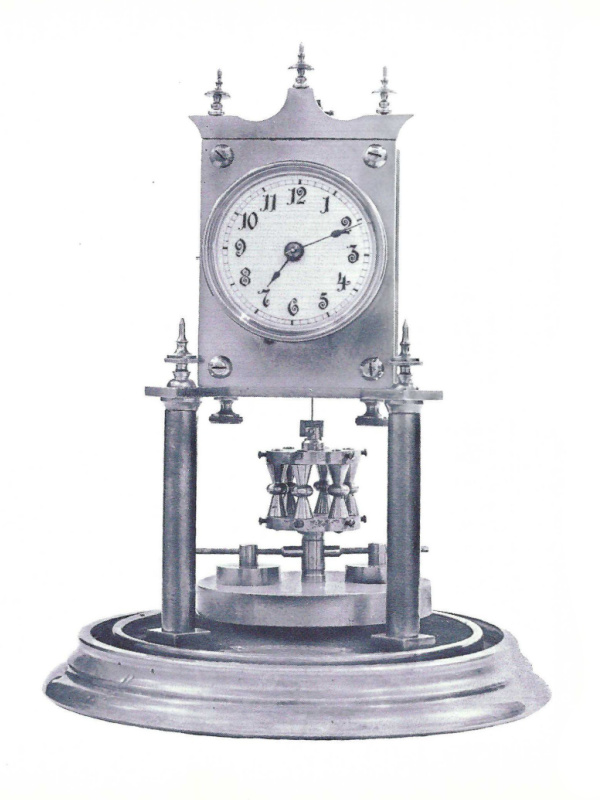

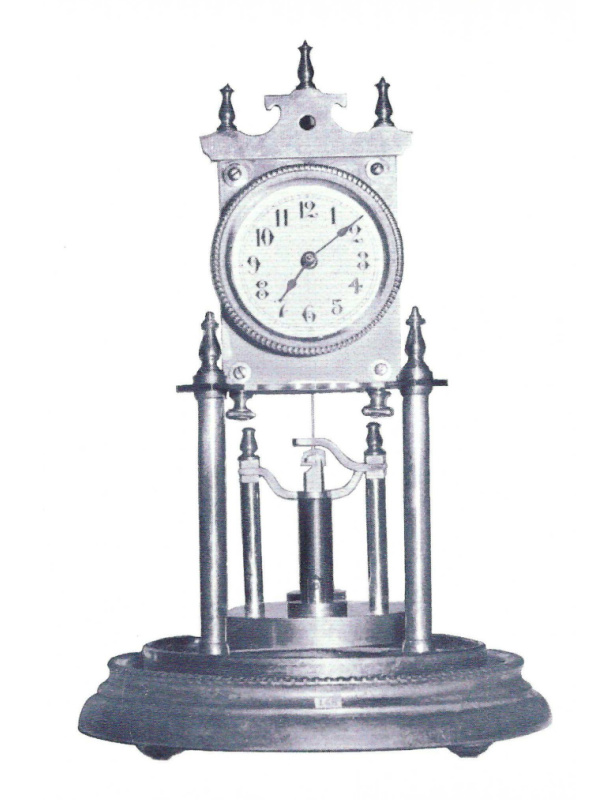

No. 2

1885

Here is a beautifully made clock. Its wheels and pinions are of such fine design that the movement is more typical of French workmanship of the period than German. However, the overall design of this striker so closely follows the time-only clock on the previous page that there seems to be no question about the fact that it was also made by Jahresuhrenfabrik. Around the center of the dial are the words

400 DAY STRIKE

DE GRUYTER’S PATENT

Some light on the question of where the name “400-Day Clock” originated is shed here, for this is the earliest known use of the term. It’s in English on a dial of a “Year Clock” made in Germany, and patented by a man from Amsterdam. F.A.L. De Gruyter’s German patent on this striking 400-Day Clock is number 29,348 and is dated May 18, 1884. (See appendix- page 140.)

In addition to having all of the fine points mentioned for Clock No. 1, this striker model is unique in that it has the original glass dome to fit the base which has an unusual, almost elliptical shape.

As the illustration shows, the strike is on a bell. The movement has a Graham “dead beat” escapement.

No. 3

1888

This is the same model as the preceding clock except that its strike is on a gong rather than on a bell. Also, the wooden base, with its oval dome, shown here, has been temporarily substituted for the original.

It is quite possible that not more than six or eight of these early, full-striking 400-Day Clocks are in existence today.

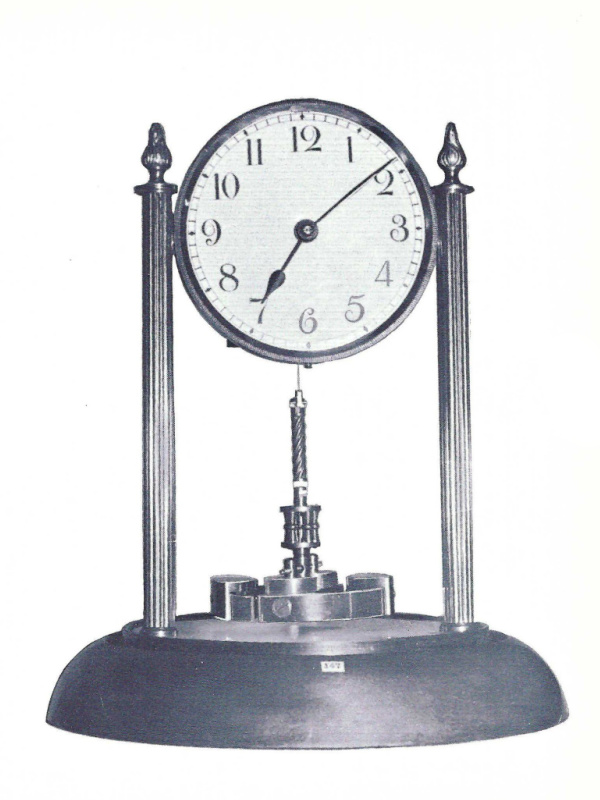

No. 4

1898

Representative of the most intricate striking 400-Day Clocks ever made are this clock and the one that follows. Their complexity lies in the fact that their escapements are duplex rather than Graham.

The duplex escapement, which was designed especially for torsion pendulum clocks, was covered by several patents under the name of Johann Christian Bauer of Furth, Bavaria, Germany. (German Pat- ent No. 90846 of October 18, 1895; British Patent No. 6356 of July 4, 1896; British Patent No. 427 of January 6, 1897; and Swiss Patent No. 15752 of November 8, 1897.) (See appendix-page 128.) The movements are somewhat larger than Clocks Nos. 2 and 3 and are somewhat heavier in construction.

Regulation is made by the turning of a small knurled nut in the hook at the top of the pendulum, which shortens or lengthens the suspension spring.

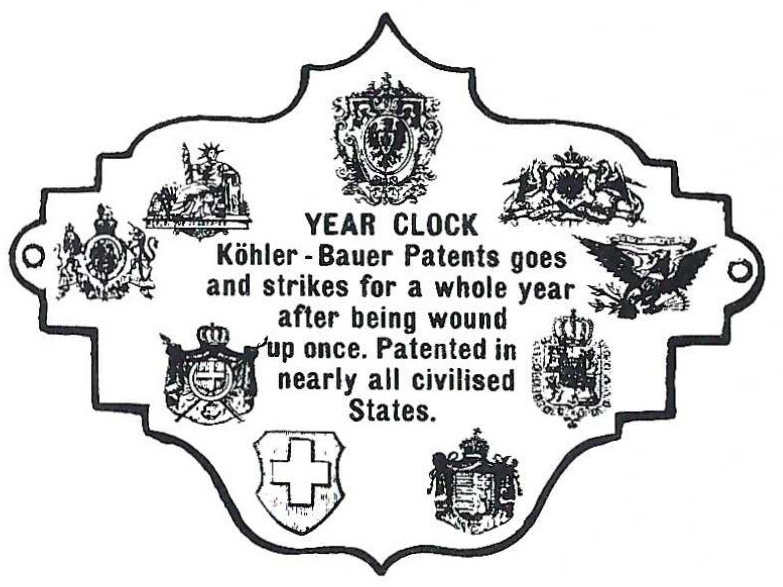

A wall clock with this same movement is in the collection at the New York University Museum of Clocks and Watches, New York. Its wooden case contains this enameled placque:

This proves beyond question that Bauer was a business associate of William Köhler who held a patent on another type of duplex escapement for this clock. (See appendix-page 129 and Clock No. 5.)

No. 5

1898

The main distinction between this clock and the preceding one is that the escapement, although still duplex, is of an entirely different, and even more complicated, design.

There is no reason to believe that this clock is any better or worse timekeeper than the clock preceding it, for as explained in the section devoted to “Striking 400-Day Clocks,” the problem with the strikers was not one of escapement.

Individual patents on this escapement are recorded in the names of both J. Chris- tian Bauer of Furth, Bavaria, Germany (German Patent No. 84582, of March 27, 1895) and Wilhelm Köhler, also from Furth (Swiss Patent No. 10519 of May 11, 1895, and British Patent No. 9560 of July 6, 1895). (See appendix-pages 128, 129 and 130.)

The name “Jahresuhr Sylvester” appears on the back plate of this clock; the name “Sylvester” on the dial. Sylvester striking 400-Day Clocks were made by Jahresuhr-Uhrenfabrik C. Bauer, Furth, Bavaria, which was founded in 1893. Their clocks were exhibited at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1900. The only other 400-Day Clock exhibitor listed in the official catalogue of this exposition was Jahresuhrenfabrik G.m.b.H. Although Ph. Haas & Söhne of St. Georgen, Germany, one of the early 400-Day Clock manufacturers, was also represented, apparently they did

not exhibit 400-Day Clocks.

No. 6

1895

Although the specific clock pictured here was originally sold by F. Zacher & Co. in Berlin (the name is on a plate mounted on the base of the clock), it was an exact model of it that was first imported into the United States. It is very similar in design to Clock No. 1, the major change being in the pendulum which has the now familiar crown design above the disc.

Like most early clocks, this one, too, has no suspension spring guard, and no “peepholes” in the back plate to make it possible to observe the drops and locks of the escape teeth on the pallets.

No. 7

1902

This clock is an early example of a “midget” model of the same (unknown) manufacturer who made Clock No. 6.

As early as June, 1903, both “Year-Long Clocks” and “Midget Year-Long Clocks” were being advertised. These first midgets were only slightly smaller than the standard size clocks, the reduction in size resulting from the use of shorter pillars and, in some cases, by a smaller diameter base. There was no change in the size of the movement.

This “midget” clock is only 21/2 inches smaller in height, and the base is only one inch smaller in diameter than the standard size clock.

A few years later, miniature clocks were made with actual miniature movements. (See Clock No. 10.)

No. 8

1902

Gustav Becker was a prolific manufacturer of 400-Day Clocks prior to World War I and to some extent afterward. His organization was purchased and absorbed by Gebr. Junghans in 1927.

The movement of the clock shown here is extremely close to that found in Clock No. 6. The main difference is in the top of the base which, in this model, is manufactured of one die-stamped piece of brass.

Three different trademarks are to be found on the back plates of Becker clocks. In this model, note the two circles in the center of the back plate. The left one carries the words “GUSTAV BECKER” at the top, the initials “G B” with an anchor between them, and “FREIBURG IN SCHL. (Schlesien)” at the bottom. In the right circle is “MÉDAILLE D’OR.” It is not clear where the model earned a gold medal award, although it was probably in one of the Paris Expositions of 1900 or 1910. However, Becker is not listed as an exhibitor in the official catalogues of these fairs. Another Becker trademark has just the anchor with the initials “G” and “B.” Still another merely has the words “GUSTAV BECKER GERMANY.”

This early Becker model did not have a suspension spring guard. A later model, which was originated about 1905, is shown with the guard in Becker’s instruction sheet. (See appendix-page 139.)

No. 9

1899

The major feature of this clock is the bi-metal, chronometer-type “temperature compensating” pendulum. It is actually a crude version of “a chronometer balance known as a ‘Guillaume’ or ‘integral’ balance, one which is able to compensate almost perfectly for the change in stiffness of a steel balance spring of a chronometer with changing temperature.” (F. A. B. Ward in Time Measurement.) Swiss Patent No. 5172 for this pendulum was issued to J. J. Meister of Paris on June 22, 1892. (See appendix-page 125.)

A notable feature of this clock, the first of several changes that were made over a period of years, is the design of the suspension unit pivoting point, commonly referred to as the suspension “saddle.”

The arrangement of this saddle has been credited to one F. Dauphin. (See appendix -page 134 for a detailed drawing.) In this saddle, the pendulum hangs perfectly straight even though the clock is leaning slightly forward or backward. The design, however, does not provide for the side-to-side levelling of the clock. Still, it helps prevent the spring from being bent, regardless of the direction in which the clock is tilted. Subsequently, a true gimbal design was perfected which allowed the pendulum to hang straight even though the clock was not exactly level in any direction. (See Clock No. 17 and appendix-page 134.)

No. 10

1900

This clock may well have the first, true miniature movement. However, one wonders why the miniature movement was placed on a standard base and platform, for the resulting effect makes the clock decidedly bottom-heavy.

From the appearance of the back plate and the semi-adjustable suspension saddle, it seems obvious that this clock was made by the same manufacturer who produced Clock No. 9.

No. 11

1903

This clock represents another example of a manufacturer’s attempt to solve the timekeeping problem by means of a temperature compensating pendulum.

The suspension spring passes through a thin slot in the bent arm at the top of the pendulum before it is hooked on to the pendulum proper. As the temperature increases, the arm bends upward slightly. The resultant shortening of the spring has the effect of speeding the clock up. At the same time, the heavy brass disc of the pendulum expands, slowing the clock down. In theory, the two actions compensate for each other but, in practice, the pendulum acted more as an excuse for competitive sales promotion than it did for making the clock better timekeeper.

German patent No. 144687 on this pendulum was recorded on April 2, 1902, in the name of Louis Willie of Leipzig, Germany. However, the production design differs considerably from the original patent illustration. (See appendix-pages 132 and

133.)

Clocks with this pendulum were first advertised in the United States by Geo. Kuehl & Company, Chicago, in June, 1904. 1049 and 1053 in the Horolovar 400-Day (D.R.P. 144687 appears on Back Plates No. Clock Repair Guide.)

About a year earlier, in June, 1903, another advertisement of Geo. Kuehl contained an illustration of a clock showing a new “temperature compensating” pendulum design which was apparently

an artist’s conception of the pendulum in Clock No. 35. (See appendix-page 126.)

As the illustration shows, the strike is on a bell. The movement has a Graham “dead beat” escapement.

No. 12

1904

This is another clock made by Jahresuhrenfabrik. It is similar to Clock No. 1, but with many improvements and refinements. There is reason to believe that this particular model was made for the English market, because dials with flowered gar- lands were not popular in the United States until a later date.

Except for the garlands and the special pendulum, it is also similar to Clock No. 202a in the 1905 Jahresuhrenfabrik catalogue.

The most interesting aspect of this clock is that it exemplifies Jahresuhrenfabrik’s attempt to make it a better timekeeper through use of their own “temperature compensating” pendulum. In this design, the expansion and contraction of the pendulum arms are supposed to cancel out the expansion and contraction of the balls, there-by providing perfect compensation. But this design did not result in making the clock keep better time for the same reason that other “temperature compensating” pendulums failed.

It is not clear when the first ball pendulums appeared, or which manufacturer first used them. However, it was probably Jahresuhrenfabrik, about 1902. Subsequently most of the industry conceded that the ball pendulum was not only more attractive but, because it concentrated relatively more weight on its periphery than was possible with the disc pendulum, it also helped to decrease the changes in pendulum momentum caused by temperature variations.

No. 13

1901

The Kienzle Clock Factories were the first to manufacture 400-Day Clocks with pin pallet escapements. These models also had lantern pinions with rods of the fixed, rather than the rolling, type.

The lower cost of production of the pin pallet escapement models is reflected in their lower wholesale prices.

Clocks with pin pallet escapements and lantern pinions have always been frowned on by repairmen. The pallets are easily broken if an attempt is made to adjust them, and the pinion rods, even if imperceptibly bent, will bind on the wheel teeth.

Most of the clocks in the Kienzle catalogue which illustrates this model have Graham escapements, with solid pinions throughout.

No.14

1910

Although “HUBERUHREN” is stamped in the back plate of this clock, the model has the same pin pallet escapement movement as Clock No. 13. It is illustrated as No. 202 in the 1910 Kienzle Clock Factories catalogue. The name “HUBERUHREN” is also to be seen on models with Graham escapements which may have been manufactured by Kienzle or possibly by Jahresuhrenfabrik who was also known to have manufactured clocks with the Huber name.

Since Andreas Huber has been credited with being an early 400-Day Clock manufacturer, it would be interesting to know why he felt it necessary to become so closely associated with Kienzle and Jahresuhrenfabrik. A conjecture would be that Huber discontinued the manufacturing of the clock, but continued to market clocks of other manufacturers under his name.

This particular model was made to sell at the lowest possible price. Kienzle called it the “Eureka,” and used the following copy in their September, 1913, advertisement-

“The increasing popular demand for four hundred day clocks impelled us to place on the market one that would be Very Cheap and of Higher Quality.”

The disc pendulum crown is made of a die-stamped strip of thin brass, bent into a ring, and held in place by two brass collars. The pendulum disc is made of a thin brass veneer over an iron cap.

The arch is die-stamped sheet brass with right-angle bends providing platforms for

the finials.

The dial is of heavily lacquered paper. Many a repairman has come to grief when he has attempted to eliminate age discoloration of this dial by dipping it in cleaning solution!

No. 15

1919

This is Kienzle Clock Factories’ Model No. 292. Only five inches high, it is described as a “Miniature 400-Day Clock” in their catalogue, but it would have been more accurate to describe it as a 30-day clock.

It has a pin pallet escapement and a marble base. It also has regulating weights within the bob, which may be moved in or out by the turning of a knurled nut at the top of the pendulum.

This clock probably holds the record for being the smallest torsion pendulum clock

ever made.

No. 16

1899

This gesso-cased 400-Day Clock is somewhat of a mystery, for there is nothing like it illustrated in any available catalogue or importer’s advertising. Yet it does not have the appearance of being one of a kind. A guess might be that the model had a limited production for sale to Europeans, whose decorative taste leaned toward Italian, Austrian or other gesso-applied furnishings.

The quality of the movement, the pendulum and the entire installation of the clock in the case is excellent.

A box-shaped brass cover fits over the en- tire movement, keeping it free from dust. The cone-shaped pendulum is distinctive and most unusual.

No. 17

1904

This clock exhibits three examples of early basic changes in the design of 400. Day Clocks: the gimbal type of suspension, the two-ring suspension spring guard, and the escapement observation “peepholes.” The gimbal suspension (see appendix- page 134) is still unnecessarily complicated, although it was an improvement over previously designed fixed and semi-fixed pivoting points of the suspension spring.

The two-ring suspension spring guard was designed originally as a part of the gimbal suspension. However, the rings were continued for a period on some models even after the gimbal suspension had been abandoned. The rings did help to prevent the suspension spring fork from becoming detached from the anchor pin if the clock were not carried carefully. They also were an aid to the leveling of the clock.

The two escapement “peepholes” first appeared in back plates about 1904. It is rather surprising that it took 14 years for someone to suggest them, for the holes made it possible to obtain a perfect view of the “locks” and “drops” of the escape teeth on both the entrance and exit pallets. Previously, all escapement adjustments had to be made from the sides of the movement, from which positions it was almost impossible to get a good view.

It was several years before the peepholes were universally adopted by all manufacturers, so it is not possible to pinpoint the date of manufacture of a clock by their presence.

No. 18

1908

Other than by the rococo design of its front, this clock differs very little from Clock No. 17. The movement is exactly the same, but the dial, pendulum and base are of somewhat later vintage.

The name “Fortuna” on the dial was the trade name of a German manufacturer. Fortuna clocks were imported in 1908 by Theodore Schisgall of New York, whose slogan for them was “Foreign Make American Guarantee.”

No. 19

1903

The movement of this clock is exactly the same as No. 17 and No. 18, but with two interesting features added: a new design of the suspension spring saddle and the 3-ball pendulum. (It is doubtful if the pendulum shown here really belongs with the clock.)

The saddle supports a single ball bearing on top of which the suspension unit is pivoted. The construction is not as complicated as the gimbal suspension shown in Clocks No. 17 and 18, yet it is equally effective. For some reason, however, it enjoyed a short life and only a very few clocks with this type of suspension are to be found today.

There were at least three different, early designs of the 3-ball pendulum. A similar pendulum is shown in Clock No. 27, the difference being chiefly in the way provision has been made for regulation.

A lighter weight 3-ball pendulum is shown with Clock No. 39.

No. 20

1905

400-Day Clocks in brass (or wood) and beveled glass cases were first promoted in the United States by Otto Young & Co., a Chicago importer, in 1903. Most of these early square-cased models had their movements supported from the bottom with two pillars similar to the models with glass domes. (See appendix-pages 126 and

127.)

This is one of the early wooden-cased models imported by Sussfeld, Lorsch & Co., New York. It carries the manufacturer’s trade name “URANIA” and was sold by Mermod, Jaccard & King, leading jewelry store in St. Louis.

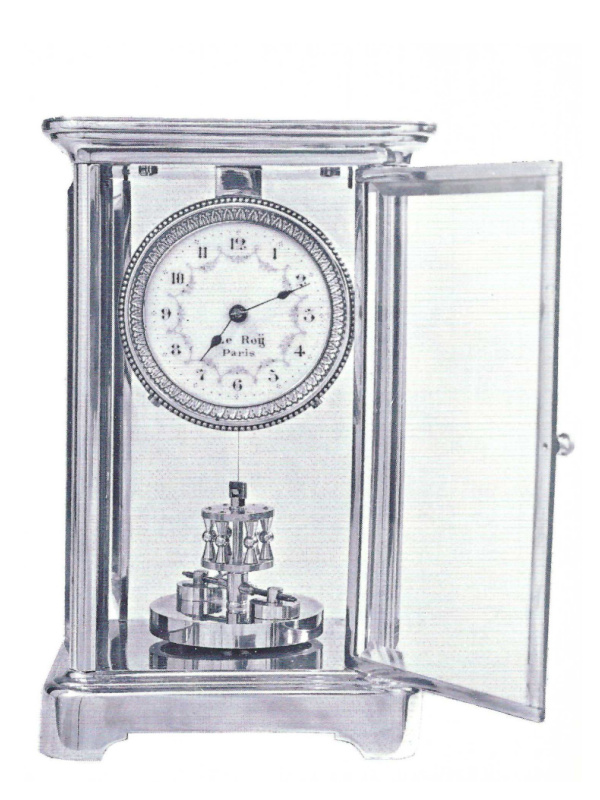

No. 21

1899

This clock has several unusual features. The first is that the movement has round, rather than square, plates. The reason for the round plates is not clear, but they have a certain aesthetic appearance which might tend to suggest that they were of a better quality than the square movements. The fact is that there is little, if any, difference. There are six clocks with round plate movements in the collection. Four different designs are represented, possibly from four

different manufacturers.

Note that this clock has the gimbal suspension bracket without the 2-ring suspension guard.

The distinctive pendulum with this clock was made about 1905; therefore, someone must have substituted it for the original which was undoubtedly of the more popular but simpler design.

No. 22

1905

This model was illustrated in the 1905 Jahresuhrenfabrik catalogue as No. 262 and reveals the fact that Schatz was one of the makers of round plate 400-Day Clock movements. This is a very fine miniature clock, only 81/8 inches high. The case has all of the characteristics of French manufacture and could have been one of a type which Jahresuhrenfabrik was known to have purchased in France.

The clock illustrated was made for the French market, and sold by Le Roy of Paris. The dial is beautifully painted with flowered garlands.

The same model was also sold in the United States by leading jewelry stores. One name which may be frequently seen on the dials is Bailey, Banks & Biddle (Philadelphia). However, the dials on these clocks are very plain, having black numerals on a white enamel background, as illustrated in the 1905 Jahresuhrenfabrik

catalogue.

A feature of this clock which often seems to go unnoticed is the extra wheel and pinion in the wheel train. It is between the center wheel and the escape wheel.

No. 23

1904

This clock has exactly the same movement as No. 22, but its refinements are hidden in this style of “louvre” case, which enjoyed some popularity for a few years. It is approximately 4″ shorter than the regular sized “louvre” 400-Day Clock. (See Clock No. 27.)

No. 24

1910

Someone apparently decided that a pendulum designed to look like a steam engine governor would make this clock unusually attractive. Regulation of the “governor weights” is controlled by a nut in the center of the pendulum.

The clock was made by Gebr. Junghans in Schramberg, Germany, (Model No. 6518) and was first advertised in the United States, in October, 1910, by Kuehl Clock Company, Chicago. It was promoted as having a “New Compensating Pendulum.” The curved scales shown on this pendulum were added later; the original did not have them.

The pendulum guard on this clock is of the first practical type to be developed. In use on some clocks as early as 1905, it is attached to the back plate by two small screws. The entire suspension unit can be removed easily through the slot which runs down the entire length of the tube. (See illustration in appendix-page 134.) The guards served their greatest usefulness during shipping. In the original factory pack, there was a brass cup which fit onto the flanged bottom of the guard, to protect the end of the spring. Most of these little cups were discarded by the buyer as soon as the clock was unpacked. (One of them may be seen resting on the base of Clock

No. 45.)

The guards themselves were thought to have little purpose, and many repairmen did not replace them after servicing the clocks. A threaded screw hole above the anchor pivot hole and another below the center wheel pivot hole are the tell-tale signs that a guard was at one time

attached.

No. 25

1904

This is a very nicely cased clock quite similar to Clock No. 26 except for the fact that the movement is hung from the roof of the case rather than from the bezel, and the movement plates are of the more common shape. The chronometer type compensating pendulum was described in Clock No. 9.

No. 26

1906

After the first appearance of wood (or brass) and beveled glass cased 400-Day Clocks, the movement support was changed to the style of French 8-day clocks. That is, the bezel was firmly attached to the roof and front sides of the case, as in this example. The heavy, brass dial-backing to which the movement is attached is inserted into the back of the bezel, bayonet fashion. It is locked in place with a thumbscrew threaded through a hole in the bottom of the bezel.

Illustrated here is an example of a high quality cased 400-Day Clock.

It is a German movement in a French-made brass and beveled-glass case. The movement is stamped “Germany,” the case is stamped “France,” and the dial is marked “Made in France.” Many other similar 400- Day Clock cases do not have French markings, yet appear to have all the evidence of, and probably are of, French manufacture.

Since the retail price of this type of clock was considerably higher than that of the popular models with glass domes, the clocks were sold chiefly through the better jewelry stores across the country. The most frequently seen names on the dials of these 400-Day Clocks are Tiffany & Company J. E. Caldwell (Philadelphia). Tiffany’s (New York), Bailey, Banks & Biddle and name may also be seen stamped on a movement back plate, but only quite rarely. For other quality clocks, see Nos. 22, 28, 29 and 30.