The Horolovar Collection more info – pg 2

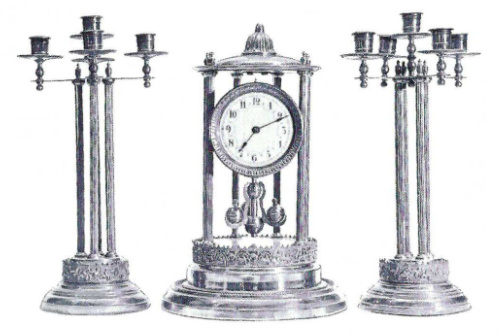

No. 27

1906

French 8-day Clock “Sets” (a mantel clock with two matching candelabra) had been popular mantel adornments all during the 19th Century. The pictured 400-Day Clock Set of the so-called “louvre” design must have been designed only for homes where there were wide mantels, for the clock’s base is nine inches wide.

The “louvre” style of clock, without candelabra, was made by three or four different manufacturers. These were about the largest mantel 400-Day Clocks ever made. The glass domes are 71/2 inches in diameter and 16 inches high. They may be found with disc, 3-ball or 4-ball pendulums, the latter being the most popular. A 3-ball pendulum of somewhat different design may be seen in Clock No. 19.

Although the top of the “self leveling” suspension unit cannot be seen clearly in the photograph, a drawing of it appears the appendix-page 134. This arrangement has been credited to Andreas Huber of Munich. Unquestionably the most complicated of them all, it yet filled the ideal requirement of insuring that the suspension spring would hang straight even though the clock were not perfectly level. This self-leveling unit was used quite extensively by one or two manufacturers and it is not uncommon to find them on clocks today. However, manufacturers subsequently learned that the same results could be obtained by other, simpler methods.

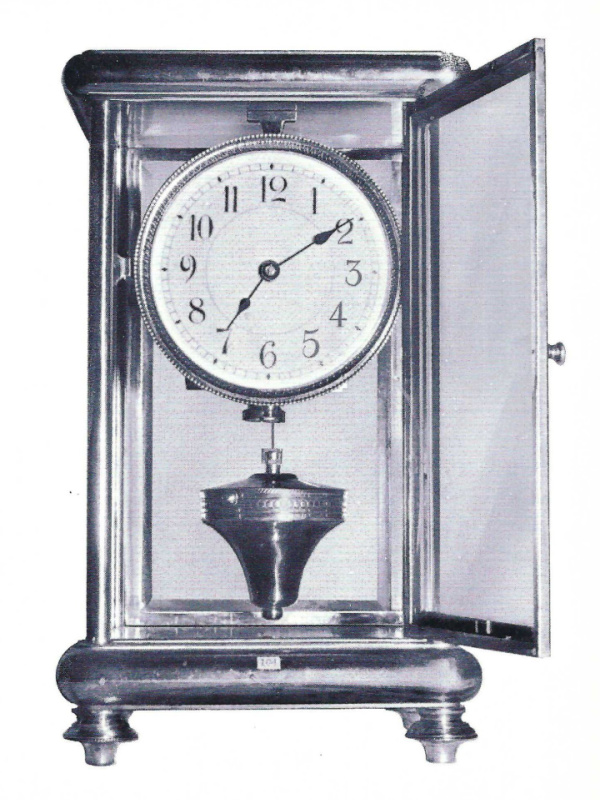

No. 28

1908

This clock has a quite heavy brass and beveled-glass case. Its pendulum is of an unusual “inverted bell” shape. Regulation is made by means of two weights on the inside of the bob which may be brought inward or outward by the turning of one the knobs on the pendulum’s periphery.

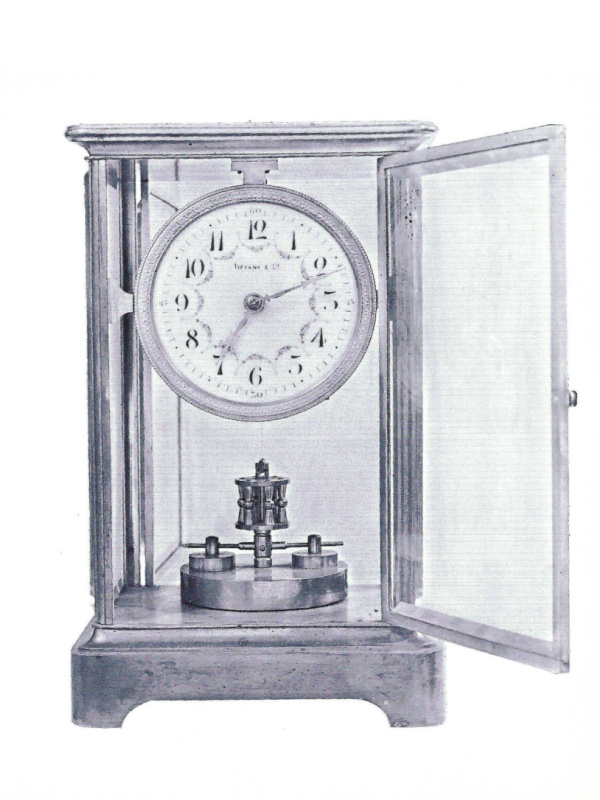

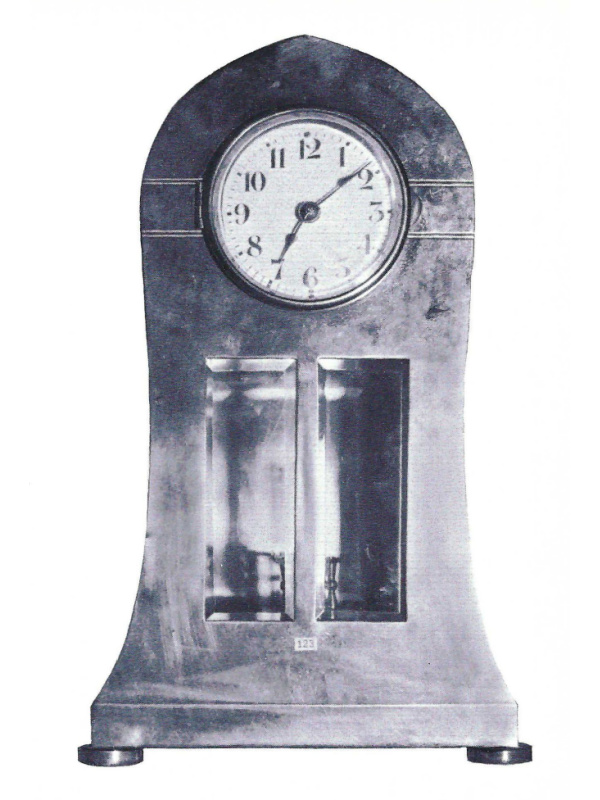

No. 29

1910

Here is another high-quality 400-Day Clock. It was originally sold by Tiffany & Company. The dial is particularly beautiful because of the fine coloring of the flowers in the garlands at the sides of the numerals. Tiffany purchased 400-Day Clocks from several different manufacturers, and some movements with round plates are to be seen in clocks with the Tiffany name.

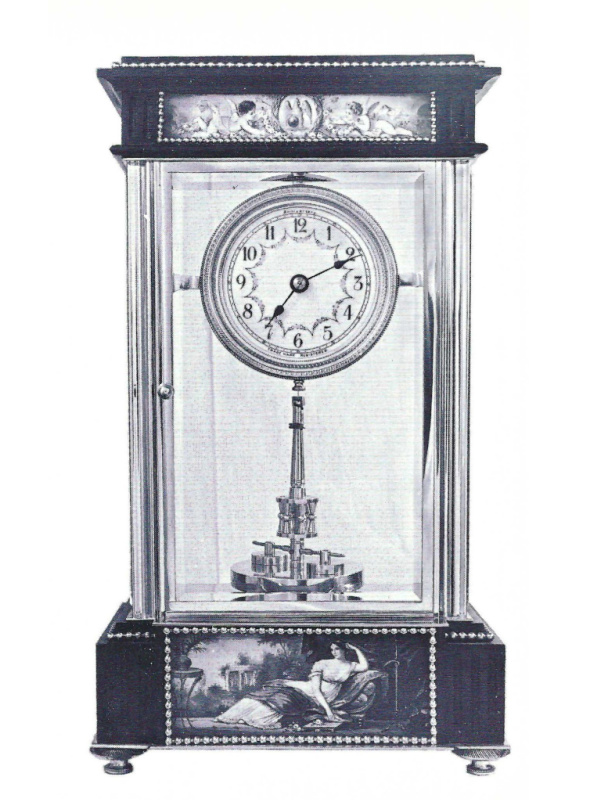

No. 30

1904

One of the most attractive 400-Day Clocks in The Horolovar Collection. The handsomely proportioned case of brass and heavy beveled glass is given added height by its mahagony base and top, both accented by lines of gilded brass beading and delicately colored enamel insets signed by “Poiterivy.” In the top panel are two putti with garlands of flowers on either side of an eagle circled by a laurel wreath on crossed arrows and, in the lower one, a graceful female figure in Grecian dress reclining on a chaise lounge, a jardiniere on a table at her feet and a circular temple in the wooded distance.

An interesting feature of the clock is the elongated cone above the pendulum. This extension not only makes the pendulum’s proportions conform with the unusual height of the case, but it also makes it possible for the suspension spring unit to be of normal length.

The movement and pendulum were made by Jahresuhrenfabrik. The case was made in Paris for Bowler & Burdick Co. of Cleveland, Ohio, the exclusive importer and assembler, whose wholesale price for the clock in the early years of the century was

a substantial $65.00.

No. 31

1904

This is another Bowler & Burdick “Anniversary Clock.” It was first offered for sale in the February 1904 issue of “The Keystone,” with either an “Italian” or “Tennessee” marble base.

At the same time Bowler & Burdick offered a “catalogue of fifteen other styles.”

No. 32

1905

The most outstanding feature of this model is obviously the case. It is listed in the 1905 Jahresuhrenfabrik catalogue as No. 233. Although a standard size glass dome is used to cover the clock, the wider base and roof with removable helmet shaped top gives it an over-all heavier and sturdier appearance than the regular standard clock.

The dial of this clock carries the name “S. Kind & Sons Phila..,” one of Philadelphia’s leading jewelers. The manufacturer’s trade mark “Urania” appears at the top of the dial which indicates that it was imported by Sussfeld, Lorsch & Co., New York.

No. 33

1905

The “grandfather clock” type of dial on this clock is its most noteworthy feature. The dial is in one piece and, therefore, was much less expensive to produce than the contemporary enamel dials with bezels. It can be assumed, therefore, that this model was made to sell at a competitive retail price. It was listed as No. 234 in the 1905 Jahresuhrenfabrik catalogue.

No. 34

1910

This case of lacquered brass with beveled glass panels was not a popular 400-Day Clock model in the U.S. However, brass cases were being promoted by U.S. clock manufacturers at the time.

Sessions Clock Company, for instance, was promoting 8-day “Genuine Brass Clocks” in 1910 and, at about the same time, E. Ingraham Company was featuring a line of alarm clocks in all-brass cases.

No. 35

1905

The “twin loop” temperature compensating pendulum on this clock was used by several manufacturers as an extra feature available at an added charge. In the U.S.. it was promoted first by Sussfeld, Lorsch & Company, New York, in August 1903. (See appendix-pages 126, 128 and 131.)

As licenses to use this pendulum were given to manufacturers, it was apparently a requirement that its patent numbers appear on the movement back plate regardless of whether or not the consumer paid the extra premium to purchase it. It is because of this that all clocks which might have been sold with the pendulum had special notation of the pendulum’s patent on the movement back plate. At first, only these words appeared: “PATENT ANGEMELDET / PATENTS APPLIED”

(See Plates No. 1471 and 1531 in the Horolovar 400-Day Clock Repair Guide.) Later, the actual patent numbers appeared: D.R.P. No. 144688; U.S.P. No. 751686

(See Plates No. 1043, 1047, 1051 and 1055 in the Horolovar 400-Day Clock Repair Guide.)

Although credit for the invention of this pendulum is usually given to Andreas Huber, of Munich, Germany, whose patent No. 144688 was recorded on April 5, 1902, a United States patent No. 751,686 by H. Sattler of Munich was recorded on February 9, 1904, using almost identical illustrations and with almost exactly the same claims. (See appendix-page 131.)

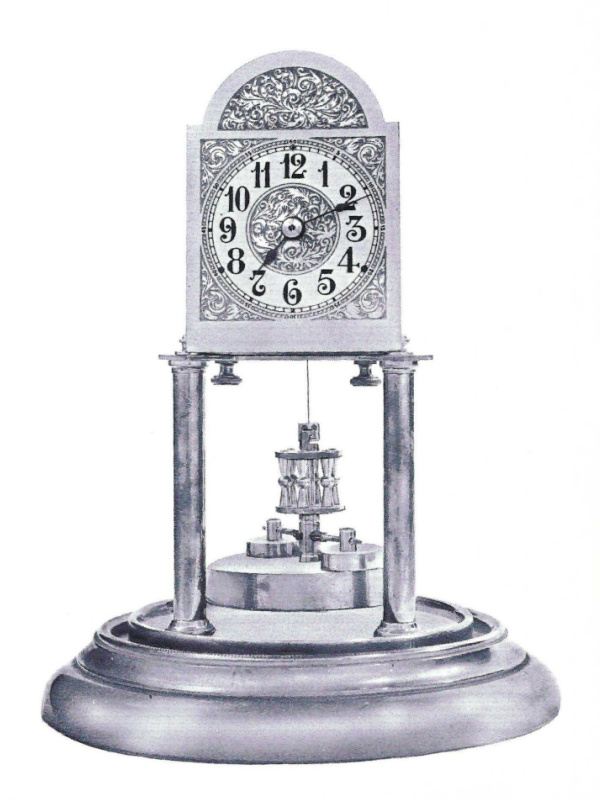

No. 36

1905

The movement of this clock is supported by four columns instead of two. The extra columns give the movement a great deal of much needed rigidity, but the design was never popular. This clock is No. 253 in the 1905 Jahresuhrenfabrik catalogue.

No. 37

1906

The pendulum is the outstanding feature of this clock. The big ball is just a decorative substitute for the crown which appears on most disc pendulum.

No. 38

1905

The wall clock models of 400-Day Clocks were not very popular in the U.S. In fact, if any were imported for sale, it would have been very few. This type of wooden case, with minor variations in design, was popular on the Continent, particularly with 8- day chime pendulum movements. With the cases in production, it was easy for the manufacturers to convert them for use with the 400-Day Clock movement.

Most of the catalogues which include 400-Day wall clock models of this type show them with large ball pendulums, probably 3″ or more in diameter. (See appendix- page 133.) The cylindrical pendulum in this clock, although of quite a different shape, has two lead weights on the inside which can be regulated by moving a lever

at the top.

No. 39

1906

This clock and the one that follows were made by Franz Vossler who was not an extensive 400-Day Clock manufacturer. This is actually a 30-day clock with a front wind movement. The “louvre” style case is proportionately tall, the glass dome size being 538 inches in diameter by 1314 inches high. Although the clock is shown here with a 3-ball pendulum, it is doubtful if it is original. (See illustration of Clock 40 for a better view of the back plate.)

Franz Vossler also manufactured standard size 400-Day clocks with round movement plates. Unlike any other 400-Day Clock, this one provides a means of removing the barrel for mainspring replacement without taking the entire movement apart. (See Plate 1144 in the Horolovar 400-Day Clock Repair Guide.)

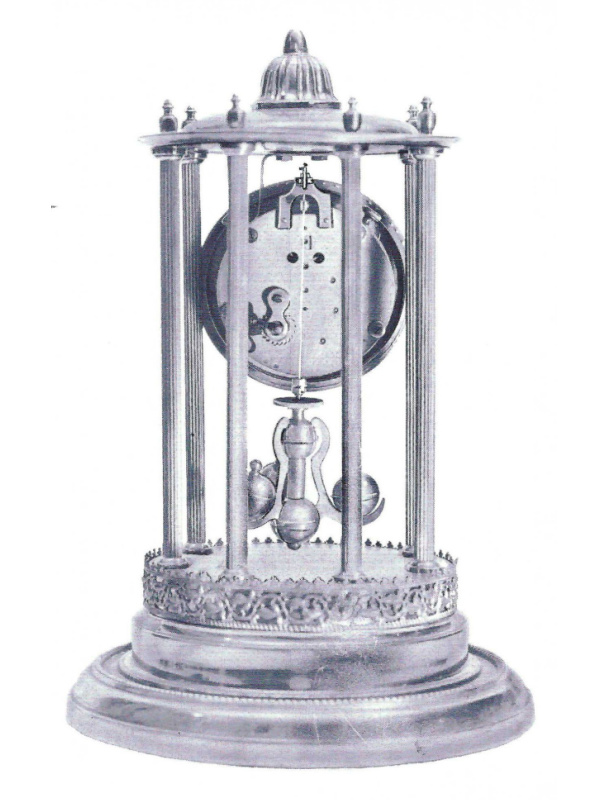

No. 40

1905

This is another Franz Vossler front wind, 30-day “400-Day Clock” in a “louvre” case. The view of the back plate of this clock more clearly exposes the arrangement of some of the movement’s features: the anchor pin extends downward from the anchor arbor; friction tight tapered pins hold the suspension spring in the saddle as well as the suspension fork onto the suspension spring.

A friction tight brass cap covers the back

of the movement.

No. 41

1904

This “louvre” front wind 30-day “400- Day Clock” was made by Jahresuhrenfabrik. The underslung anchor pin is similar to Clocks No. 39 and 40, but the suspension spring saddle and fork are of the common type. (A better view of the back plate can be seen in Clock No. 42.)

An interesting feature of this clock is the 2-ball pendulum.

A friction tight brass cap covers the back of the movement.

No. 42

1904

This clock is exactly the same as Clock No. 39 except for the different shape of “louvre” case. The photograph of the back of this movement clearly shows the underslung anchor pin and the narrow, horizontal opening in the back plate which provides space for the ends of the fork tines to clear the plate.

No. 43

1907

This skeleton 400-Day Clock, complete with skeletonized pendulum, was made by Gustav Becker (see Clocks No. 8 and 44 also made by Becker.) The wheels and pinions of the standard size movement have been repositioned in an almost vertical line in order that the structure could be made symmetrical. Note that the movement is front wind.

This model is quite rare. Apparently not many were made. It has the original dome which is of unusually heavy glass and is true oval-shaped at the base.

No. 44

1908

This model Gustav Becker clock is the only 400-Day Clock ever made which is equipped with a device for putting the pendulum in beat more easily. The photograph does not show the overhead suspension unit clearly enough to reveal its details, but a line drawing of it can be seen in the appendix-page 138. The unit involved the production of many extra parts, with resulting extra cost. It is doubtful that the average clock owner understood its value, let alone knew how to operate it.

The Becker 4-ball pendulum is distinctive because of the pointed tops of the ball caps. The Becker suspension spring guard was the first to include a locking mechanism for the lower suspension block. A detailed drawing of the guard can be seen in Becker’s instruction sheet which appears in the appendix-page 139.

Becker, incidentally, was the only manufacturer of 400-Day Clocks with back plate serial numbers running into the millions. This clock is No. 2185374, although there is no real proof that the numbers were used

consecutively.

No. 45

1904

This rather squatty clock was made by Jahresuhrenfabrik. The same model, with a higher movement, appears in the 1905 Jahresuhrenfabrik catalogue as No. 202a. This model was apparently especially made with the movement lower to look better with the chronometer type “temperature compensating” pendulum.

Note the brass piece which rests on the base of the clock. This is the original cap which fits friction tight under the flared end of the suspension spring guard. Its purpose was to protect the exposed end of the suspension spring from becoming bent during shipping. Most of these caps were thrown away or were lost after the clocks were started running. Only a few of them can be found today. (See cap in Jahresuhrenfabrik catalogue illustration in the appendix-page 134.)

The suspension saddle on this clock is not easily seen. However, it is of the type shown on Clock No. 27 and also may be seen in the same illustration in the appendix-page 134.

No. 46

1912

This is the enigma clock in the Horolovar collection. Is is the only known 400-Day Clock with calendar dials showing the day of the week (in German) and the day of the month. It is believed that this model was made exclusively for the German market.

At least one other model exists, but it does not have twisted columns, and its arch is of a different shape and narrower than this one.

The enigma has to do with the curved metal dial calibrated from 1 to 31 which is above the porcelain dial. There are two pointers (not just one!) that can be moved manually, and every clock is the same. Since there is already a day of the month dial which operates automatically with the movement, what is the need for the second dial, and why two pointers? This question has been asked of several well-known horologists, but none has come up with a likely answer. Even an advertisement or catalogue page would probably provide an explanation, but the clock was not sold in the U.S. and the manufacturer is unidentified.

No. 47

1905

This clock was probably made to follow the demand for cut and engraved glass which was being heavily promoted around the turn of the century. The all-glass base and cover are indeed different from those of other 400-Day Clocks, and they are also considerably heavier. It must have required unusually careful packing to insure that the clock would ship without breakage. It can be correctly assumed that this clock carried a premium retail price and also that it was not long on the market. It is very rare.

No. 48

1909

This is the only 400-Day Clock which is entirely French-made. (See patents in the appendix-page 137.)

Its movement and pendulum are of excellent workmanship, and they have several other features which deserve special note.

The suspension unit saddle is quite different from those of German design. Although complicated, it is nevertheless functional in every respect.

The symmetrical shape of the pendulum makes it virtually impossible for one to tell whether or not it is in motion, unless he is only a few inches away.

Eight screws under the base of the pendulum (the patent shows only four) hold strips of lead firmly on the inside, thus providing a rough means of regulation. Final regulation, however, must be made with a key inserted through a hole in the rim of the disc. The key, in turning a left-and-right threaded rod, brings two brass weights either nearer to or further away from the center.

Note the warning that appears on the underside of the pendulum. Freely translated, it reads: “To open, and to protect the pendulum’s regulation, unscrew the baluster on top. Don’t fool with anything underneath.”

It is rather incongruous to see this beautifully executed movement and pendulum mounted on such inexpensive-looking, wooden, underpinnings. Yet it is by no means unusual. In fact, they are also known to exist in a wooden cased wall clock. It would be logical to assume that, somewhere, there must be a model of this clock in a case with workmanship compatible with that of this movement and pendulum.

No. 49

1910

This ingenious torsion pendulum calendar clock is either an inventor’s model or an example of a clockmaker having some fun! It is a 30-hour clock, not a 400-Day Clock. The pendulum is the big, brass wheel which can be seen with its hub just above the base.

Note the tiny “anchor” attached to the suspension spring (indicated by the arrow) which has been designed to allow one escape tooth at a time to give it an impulse at each rotation of the pendulum.

The weight, at the present time just below the escape wheel, is relatively light. The clock’s hour hand is attached to it and registers the hours on the vertical dial as it falls. The weight also trips the calendar mechanism as it passes by on its one-day descent. The round dial shows the minutes only. Several hooks and levers turn the days and months of the calendar dial.

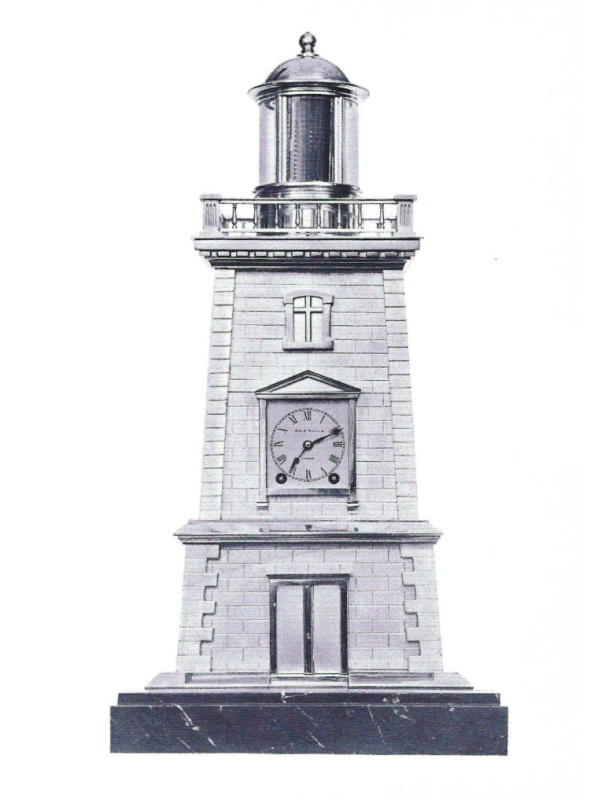

No. 50

1885

This is a beautifully constructed lighthouse clock and is one of the outstanding clocks in The Horolovar Collection. It was made in France and is operated by a 15-day movement. Its outstanding feature is that the pendulum is not only attached to the torsion suspension spring, but it is also kept in balance by a helical spring which, although very large, is similar in action to a hairspring. The design is based upon German Patent No. 21340 recorded May 17, 1882, in the name of C. E. Büssen, in Eckernförde, Germany, for a “Rotationspendel Mit Spiralfeder.” (See appendix-page 136.) Its purpose was to improve the time-keeping of a torsion pendulum clock.

The name “R. G. A. Wells, London” appears on the dial and is undoubtedly the name of the store which sold the clock. The base is red marble, the “stonework” of heavy brass.

Markings on the movement back plate

are: “MEDAILLE D’OR GLT BTE S.G.D.G. PARIS”

Bte. is an abbreviation for Brevete. (Patented). The S.G.D.G. is Sans Garantie du Gouverne (Without Government Guarantee). The GLT is so far unidentified, but might be a key to the name of the manufacturer.

No. 51

1885

This clock is a simpler version of Clock No. 50. The movement is time-only, although this model is known to have been made with a striking movement. The big, helical spring, which is one of the unusual features of Clock No. 50 does not exist with this clock, although outward appearances give the impression that it is there. This was probably the intent of the designer. The “coils” are just part of a stationary, die- stamped cylinder made to appear like the coils of a helical spring.

The roof of this lighthouse was omitted from the photograph in error, but it is similar to the one on Clock No. 50. Both Lighthouse Clocks No. 50 and 51 were originally equipped with a silver plated, brass flag flying from a pole which extended from the top of the semi-spherical roof by about three inches.

No. 52

1882

The “Mysterious” Torsion Pendulum Clock

This torsion pendulum clock, the most recent addition to The Horolovar Collection, is the only one of its type that merits being called a “mystery clock.”

In appearance, as the photograph shows, the whole thing is not unpleasing, although quite large (25 in. high), and the lines of the supporting figure (which is, regrettably but inevitably, executed in spelter) are good. The dial and numerals, blue on white enamel, are in the Louis XVI manner and, at first glance, only the somewhat coy and pained expression of the young woman betrays its unmistakably 1880-ish origin. But considering the exhausting posture she has maintained for some eighty years a pained look is, perhaps, hardly to be wondered at.